A curious paradox runs through the modern obsession with “boundaries.” On the one hand, the word has entered the lexicon of therapy culture like a sacrament, invoked with the reverence once reserved for virtues like patience or forgiveness. On the other hand, it has been cheapened, claimed by the woke movement as a shield against any intrusion of discomfort, re-cast as a kind of moral veto on the world. In such usage, boundaries no longer describe the careful architecture of a life well lived; they are simply weaponised preferences.

Psychologically, the imposition of boundaries always carries the scent of rage. A line is drawn because something intolerable has already taken place. To tell a parent, a partner, a sibling, no further, is to announce that one’s skin, one’s psyche, has been pierced. The fury comes not only from the transgressor, but from within: the child who once had no defences, the adolescent who once had no choice, now awakens in the adult voice and says—never again. Rage becomes the midwife of autonomy.

Classical psychoanalysis treated boundaries not as slogans but as thresholds. Winnicott wrote of the “good-enough mother” whose role was precisely to provide a permeable boundary – one porous enough for love, firm enough for safety. Lacan’s mirror stage reminds us that identity itself begins with a boundary: the distinction between “I” and “not-I” when the child first recognises its reflection. To lack boundaries is to dissolve into the Other; to live without them is to endure perpetual invasion.

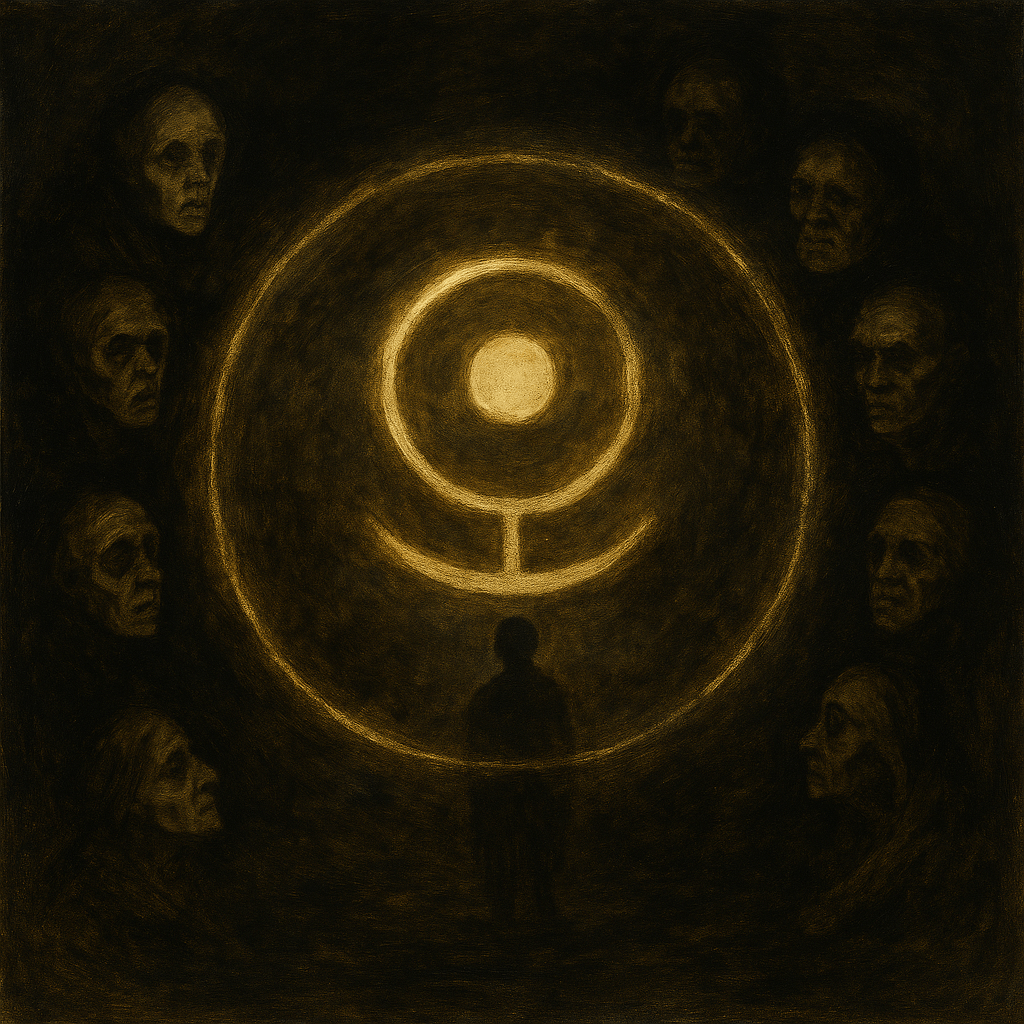

And yet, boundaries are not static walls. They are dynamic, like scaffolding: erected, dismantled, rebuilt as the psyche grows. The myth of Theseus reminds us of this: the labyrinth is not merely a prison, but a boundary that forces encounter with the Minotaur. The boundary both protects and provokes. In Jungian terms, to set a boundary is to force the shadow into the open; it is an invitation to transformation through limitation.

Why then does the imposition of boundaries so often provoke disproportionate rage in others? Because to be excluded, even gently, is to be returned to the infant’s primal wound of abandonment. To hear “you are no longer welcome in my circle” is not a social slight, it is a psychic death, an eviction from the womb of belonging. The outrage is not about the boundary itself but about the unbearable reminder of dependence.

Here lies the crucial distinction between therapeutic and counterfeit boundary-setting. True boundaries are neither punitive nor theatrical; they are simply refusals to re-enact harm. They say: I will not play this role again. In contrast, the pop-culture version treats boundaries as pre-emptive bans on discomfort. It is one thing to say, “I cannot continue this relationship because it corrodes my peace.” It is another to say, “Your existence unsettles me, therefore you must disappear.” One is protection, the other is erasure.

To cut someone out is not cruelty; it is triage. A body in sepsis cannot indulge sentimentality – it must amputate to survive. Families hate this logic because it exposes the dark inheritance: peace is rarely compatible with the compulsions of blood. To remove a parent, a sibling, even a child from one’s psychic landscape is to enact the oldest of archetypes: exile. Cain wandering east of Eden. Oedipus banished from Thebes. The community insists that such acts are unnatural. But the psyche, if it is to heal, often requires precisely this unnatural cut.

Boundaries, then, are the geometry of the soul. They carve space where dignity can breathe. They provoke rage in others because they declare the unthinkable: that love is not unconditional, that family can be forfeited, that survival sometimes requires severance.

The woke distortion treats boundaries as a language of entitlement. The deeper, older truth sees them as the architecture of freedom.

Leave a comment