He didn’t remember being sent away.

He remembered the not-coming-back.

The trunk shut. The room went quiet. A boy became a border.

At age six, a child cannot conceptualise abandonment. Not yet. What they feel instead is dislocation—a wordless confusion about where home ends and why love must sometimes be scheduled.

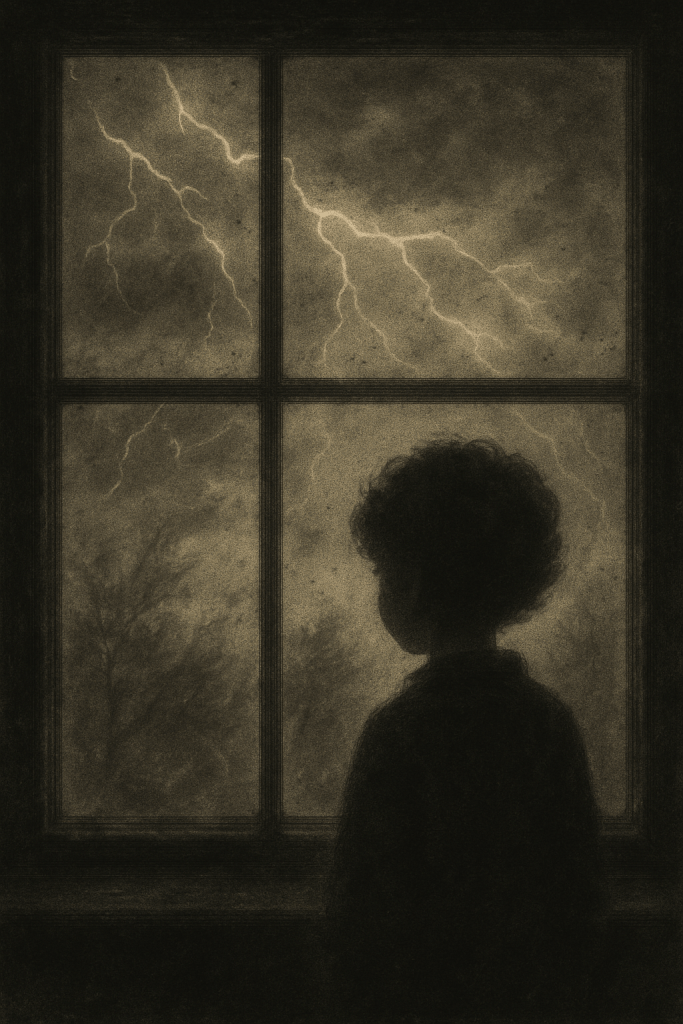

He was a weekly boarder. Meant to return each Friday. But storms are indifferent to timetables. The great tempest of ’87 grounded trains, felled trees, and left a small boy staring through leaded glass at a sky in rage. He didn’t understand why no one came.

The matron on weekends was different.

Kind, perhaps.

But kindness without familiarity is still a stranger.

He would later describe this memory not as trauma—but as atmosphere. A coldness in the limbs. A stillness around the lungs. Clinical literature on Boarding School Syndrome refers to this as “dissociative adaptation”; the child who learns to survive by emotionally disconnecting from the source of pain, particularly when that pain is institutionally sanctioned.

Lining up for chapel: a moment of peace.

Silence had shape there. Rows. Rituals. Escape.

Discipline is not always harshness. Sometimes it is relief. When the world is chaotic or neglectful, routine can feel like love. And so, he attached. Not to people (who were inconsistent) but to order. To objects. To symbolism.

The dorm hated his hamster. The boy took it home.

He began to understand that what brings comfort might cost you belonging.

There was a pencil. A hand. Blood, probably. A small violence, quickly buried. The kind of incident too insignificant for grownups and too frightening for children. He said nothing. He never learned how to say help.

Corporal punishment was legal.

Still is, in some family systems.

He remembers leather chairs and polished wood.

He does not remember who told him to bend.

Years later, during divorce, his therapist said the phrase aloud: Boarding School Syndrome. It echoed like a diagnosis but landed like a release.

It wasn’t just the separation. It was the lesson: that you must not feel too much, ask too much, or need too much— because no one is coming.

He never looked forward to going home.

Only to leaving the dorm.

The ghost of a suitcase still waits by the door.

Belonging often comes with unspoken rules: don’t be too much, don’t be different, don’t disrupt the collective harmony.

So the child adapts. Not out of wisdom, but necessity. He gives up the comfort to maintain peace. He learns to hide his needs in order to fit.

Emotional exile — is not dramatic, not punished — but slowly, quietly internalised. And it becomes a blueprint for adulthood: the person who later won’t ask for help, who gives up what soothes him to keep the peace, who performs strength instead of admitting the ache.

Navigating the borderlines.

Leave a comment