He does not cry when the door closes.

He has trained himself not to.

That training began when he was six,

when he wasn’t allowed

to bring his Easter egg home.

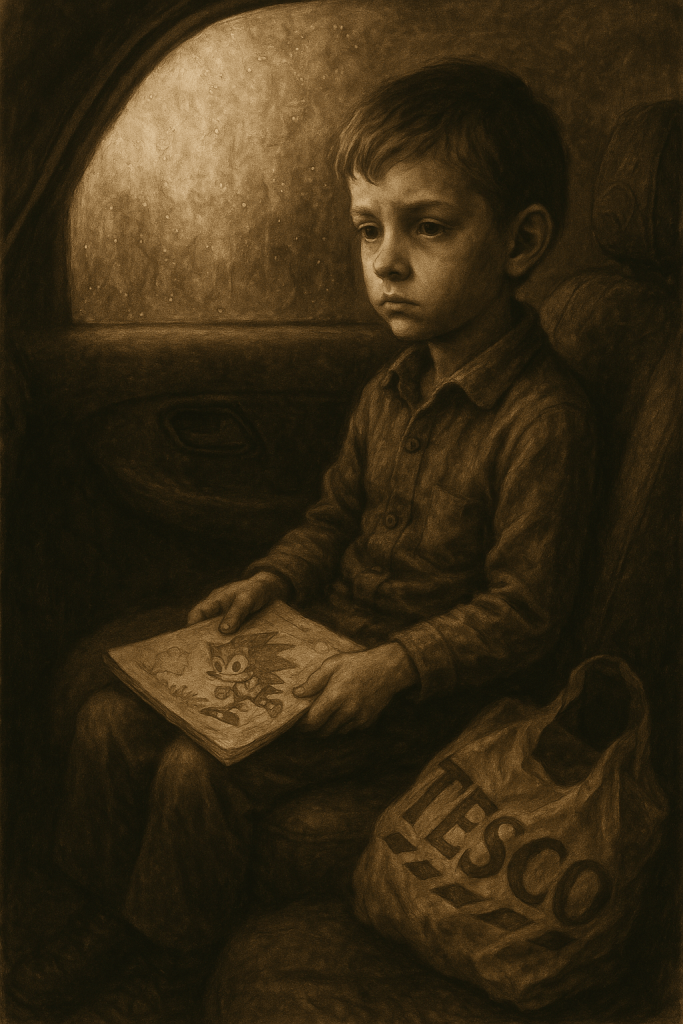

Now, at eight,

he sits up straight in the back seat of Mum’s car,

a Tesco bag rustling near his feet,

a hand-drawn Sonic scene in his lap.

He watches the steam fade from the glass

where his breath tried to write the word Dad

but stopped at D

because he didn’t want her to see.

He is going back.

Back to the house with clean countertops

and closed doors.

Where calls to his father are

disruptive,

and silence

is repackaged as consistency.

His stomach hurts every Sunday.

Every single one.

The same way it did

when Dad showed up on the wrong day.

But instead of leaving,

the teacher let them sit in the art room

just the two of them

inking monsters with bright red mouths.

It was the best day.

And it became ammunition.

He knows she thinks she’s protecting him.

That’s what everyone says.

But protection shouldn’t feel like

shrinking.

At Dad’s house

he runs,

shouts,

wrestles.

He laughs like his chest can barely hold it.

He becomes large there.

Silly, loud, real.

But by Sunday

he is already folding inwards.

Preparing for the hush.

The whisper.

The change of air.

The version of him

he has to carry back like homework

he doesn’t understand.

At school,

they give him art therapy.

He draws wolves with three eyes

and trees with broken roots.

The lady with the kind voice asks what they mean.

He says,

They’re just trees.

He doesn’t ask to call.

She wouldn’t let him anyway.

He heard Grandma’s voice

in the kitchen last week.

Not in Dad’s house—

in Mum’s.

Whispering.

Together.

Alienation is not a word he knows.

But he feels it like cold hands

in warm pockets.

He just calls it

missing someone

and not being allowed

to say it out loud.

Leave a comment